Simon ben Kosevah, or Cosibah, known to posterity as Bar Kokhba, was a Jewish military leader who led the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire in 132 CE. The revolt established a three-year-long independent Jewish state in which Bar Kokhba ruled as nasi ("prince"). Some of the rabbinic scholars in his time imagined him to be the long-expected Messiah. Bar Kokhba fell in the fortified town of Betar.

The 130s decade ran from January 1, 130, to December 31, 139.

The Hasmonean dynasty was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from c. 140 BCE to 37 BCE. Between c. 140 and c. 116 BCE the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously from the Seleucid Empire, and from roughly 110 BCE, with the empire disintegrating, Judea gained full independence and expanded into the neighboring regions of Samaria, Galilee, Iturea, Perea, and Idumea. The Hasmonean rulers took the Greek title "basileus,, and some modern scholars refer to this period as an independent kingdom of Israel. The kingdom was ultimately conquered by the Roman Republic and the dynasty was displaced by Herod the Great in 37 BCE.

The Jewish diaspora or exile is the dispersion of Israelites or Jews out of their ancestral homeland and their subsequent settlement in other parts of the globe.

The First Jewish–Roman War, sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt, or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled Judea, resulting in the destruction of Jewish towns, the displacement of its people and the appropriation of land for Roman military use, as well as the destruction of the Jewish Temple and polity.

Syria Palaestina was the name given to the Roman province of Judea by the emperor Hadrian following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE.

The Bar Kokhba revolt was a rebellion of the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, against the Roman Empire. Fought circa 132–136 CE, it was the last of three major Jewish–Roman wars, so it is also known as The Third Jewish–Roman War or The Third Jewish Revolt. Some historians also refer to it as the Second Revolt of Judea, not counting the Kitos War, which had only marginally been fought in Judea.

The Jewish–Roman wars were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of the Eastern Mediterranean against the Roman Empire between 66 and 135 CE. While the First Jewish–Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt were nationalist rebellions, striving to restore an independent Judean state, the Kitos War was more of an ethno-religious conflict, mostly fought outside Judea Province. Hence, some sources use the term Jewish-Roman Wars to refer only to the First Jewish–Roman War and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135 CE), while others include the Kitos War as one of the Jewish–Roman wars.

Eleutheropolis, was a Roman and Byzantine city in Syria Palaestina, some 53 km southwest of Jerusalem. Its remains still straddle the ancient road connecting Jerusalem to Gaza and are now located within the Beit Guvrin National Park.

Judea, sometimes spelled in its original Latin form Iudaea to distinguish it from the geographical region of Judea, was a Roman province which incorporated the regions of Judea, Samaria and Idumea, and extended over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Judea. It was named after Herod Archelaus's Tetrarchy of Judea, but the Roman province encompassed a much larger territory. The name "Judea" was derived from the Kingdom of Judah of the 6th century BCE.

Roman Syria was an early Roman province annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War following the defeat of King of Armenia Tigranes the Great.

Coele-Syria alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria, was a region of Syria in classical antiquity. It probably derived from the Aramaic word for all of the region of Syria, but it was most often applied to the Beqaa Valley between the Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges. The area is now part of the modern-day Syria and Lebanon.

Perea or Peraea, was the portion of the kingdom of Herod the Great occupying the eastern side of the Jordan River valley, from about one third the way down the Jordan River segment connecting the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea to about one third the way down the north-eastern shore of the Dead Sea; it did not extend very far to the east. Herod the Great's kingdom was bequeathed to four heirs, of which Herod Antipas received both Perea and Galilee. He dedicated the city Livias in the north of the Dead Sea. In 39 CE, Perea and Galilee were transferred from disfavoured Antipas to Agrippa I by Caligula. With his death in 44 CE, Agrippa's merged territory was made a province again, including Judaea and for the first time, Perea. From that time Perea was part of the shifting Roman provinces to its west: Judaea, and later Syria Palaestina, Palaestina and Palaestina Prima. Attested mostly in Josephus' books, the term was in rarer use in the late Roman period. It appears in Eusebius' Greek language geographical work, Onomasticon, but in the Latin translation by Jerome, Transjordan is used.

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture. Until the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism were Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria, the two main Greek urban settlements of the Middle East and North Africa region, both founded at the end of the fourth century BCE in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Hellenistic Judaism also existed in Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period, where there was conflict between Hellenizers and traditionalists.

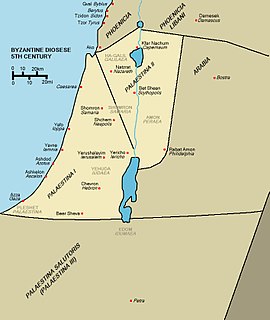

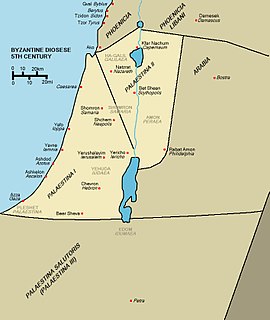

Palæstina Secunda or Palaestina II was a Byzantine province from 390, until its conquest by the Muslim armies in 634–636. Palaestina Secunda, a part of the Diocese of the East, roughly comprised the Galilee, Yizrael Valley, Bet Shean Valley and southern part of the Golan plateau, with its capital in Scythopolis. The province experienced the rise of Christianity under the Byzantines, but was also a thriving center of Judaism, after the Jews had been driven out of Judea by the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries.

Judea or Judaea is the ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous southern part of the region of Israel and part of the West Bank. The name originates from the Hebrew name Yehudah, a son of the biblical patriarch Jacob/Israel, with Yehudah's progeny forming the biblical Israelite tribe of Judah (Yehudah) and later the associated Kingdom of Judah, which the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia dates from 934 until 586 BCE. The name of the region continued to be incorporated through the Babylonian conquest, Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods as Babylonian and Persian Yehud, Hasmonean Judea, and consequently Herodian and Roman Judea, respectively.

Quintus Tineius Rufus, also known as Turnus Rufus the Evil in Jewish sources was a senator and provincial governor under the Roman Empire. He is known for his role unsuccessfully combating the early uprising phase of the Jews under Simon bar Kokhba and Elasar.

The history of the Jews in the Roman Empire traces the interaction of Jews and Romans during the period of the Roman Empire. The two cultures began to overlap in the centuries just before the Christian Era. Jews, as part of the Jewish diaspora, migrated to Rome and to the territories of Roman Europe from the land of Israel, Asia Minor, Babylon and Alexandria in response to economic hardship and incessant warfare over the land of Israel between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires from the 4th to the 1st centuries BCE. In Rome, Jewish communities thrived economically. Jews, both ethnic Jews and converts, became a significant part of the Roman Empire's population in the first century CE.

This article presents a list of notable historical references to the name Palestine as a place name in the Middle East throughout the history of the region, including its cognates such as "Filastin" and "Palaestina."

Amathus (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαθοῦς or τὰ Ἀμαθά; in Eusebius, Ἀμμαθοὺς. Hebrew: עמתו was a fortified city east of the Jordan River, in modern-day Jordan.